We Could’ve

Been Married

by Elvis

by

Caitlin Chaisson

and Denis Gutiérrez-Ogrinc

To be married by Elvis in the name of Clark County, Nevada, means one of two things and we were neither. I couldn’t persuade myself to act like someone I wasn’t, so instead I cast furtive glances at strangers wearing tiaras and t-shirts under the hallucinogenic neon lights on the Strip. I wondered if you saw me noticing the bridal parties, but you were ten paces behind and looking at something else through your camera lens. Back then you were in your aloha phase and easy to spot, even from a distance, in shirts patterned with hibiscus blooms and fenestrate leaves. We were in Las Vegas to celebrate your birthday and the one vow we made on that trip was as we boarded the airplane and promised to never go back.

![]()

I recently learned that at the Graceland Wedding Chapel, where Elvis Presley didn’t marry Priscilla Beaulieu but once pulled over on South Las Vegas Boulevard to scope it out as a possible venue, the “Loving You” package will set you back $329 not including the officiant’s fee or tips and taxes. I take this as a lesson that even the possibility of a thing that never happened is a reasonable foundation for love.

At the Graceland Chapel, the paperwork for a state marriage license must be completed before the ceremony and the betrothed must show valid government identification. In a brief fifteen minutes, the long road of life is promised to unfurl between the cursive swirls of signatures, in a blissful picture of love and togetherness until that final curtain call. Everything about the act of marriage is beguilingly anachronistic—the forever and the fleeting and the past and the future are knotted together. So, maybe being married by a man who died in 1977 but will surely outlive us all is the resounding peal of love’s complicated timelines.

![]()

![]()

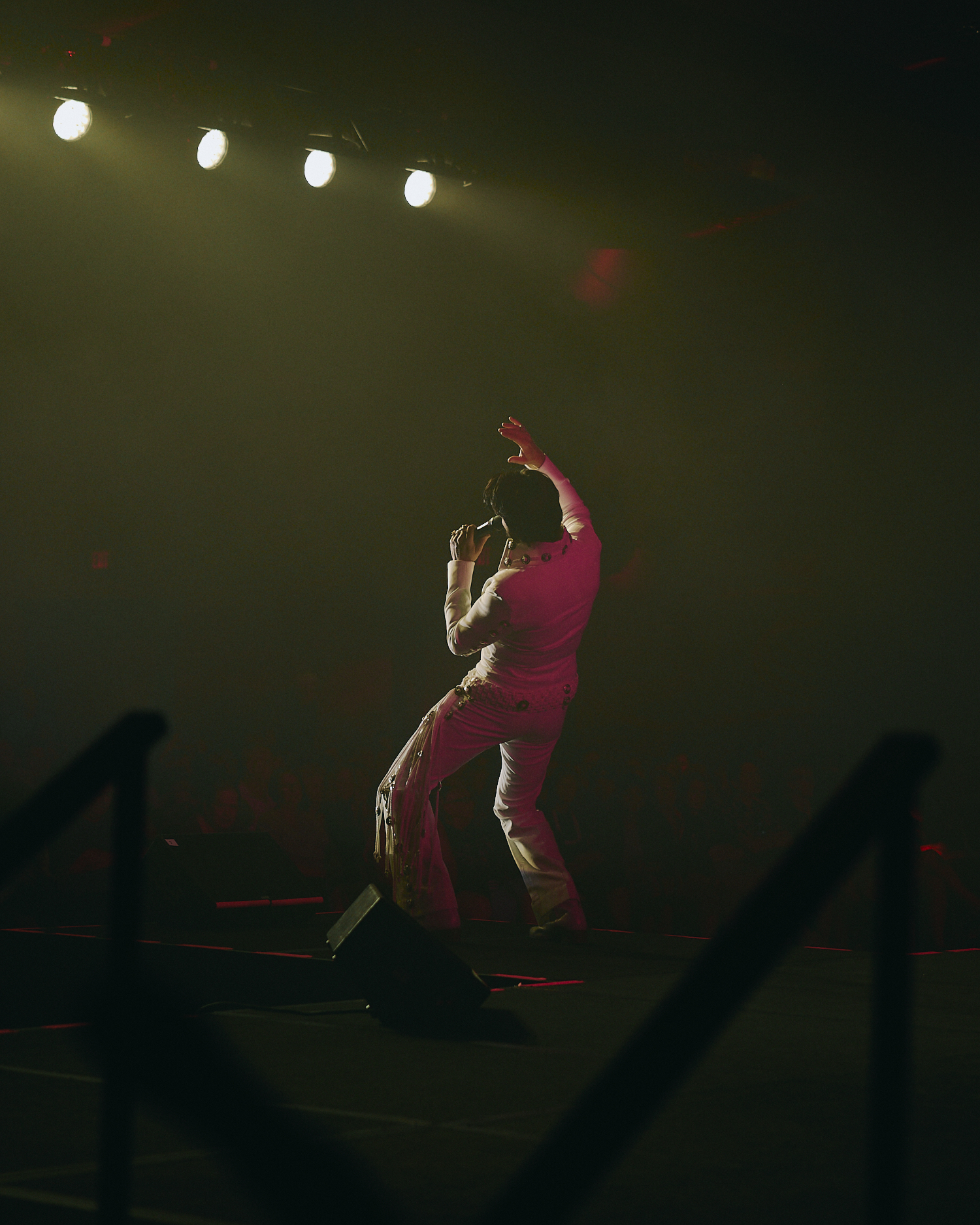

Years before we met you lived up near this place in the Okanagan in Canada that’s not famous for much but draws a crowd of people for a weekend every summer. Professional and amateur Elvis tribute artists come from all over the world to compete in qualifying rounds for the finals in Memphis, Tennessee, over two thousand miles away. Saggy folding chairs and sweating coolers dot the lawn in front of an outdoor stage with a sound system that can project the classics loud enough to be heard by the audience of silver- haired retirees and their grandchildren. The sun blazes down in the shadowless sage-brushed desert.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

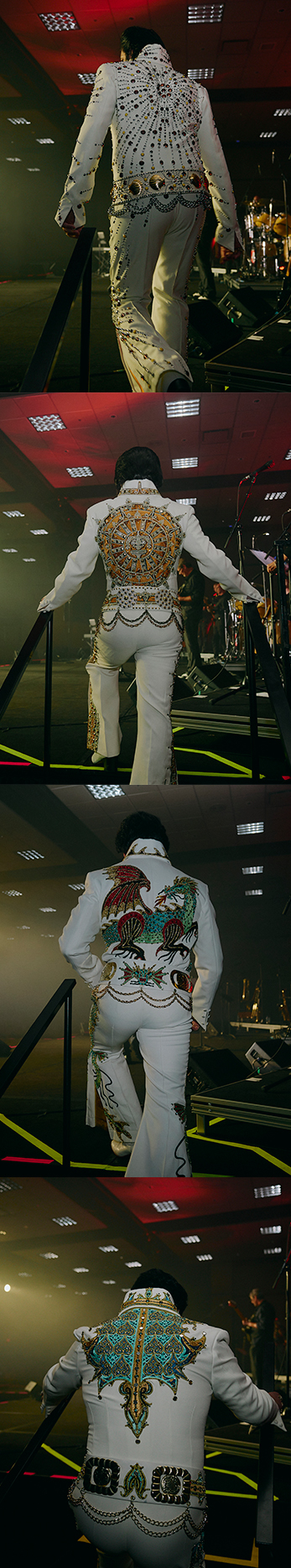

A different heat manifests in the set list of the festival’s program handout, which reads like the plot of a passionately dysfunctional relationship. The Wonder of You, Trying to Get to You, My Babe, I Can’t Stop Loving You, You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling, Suspicious Minds, If You Love Me Let Me Know, Don’t Be Cruel, Treat Me Nice, Baby What You Want Me to Do, Burning Love, I’ll Never Fall in Love Again, It’s Over, Can’t Help Falling in Love. Amidst the emotional turmoil, judgment is cast in four categories: vocals, appearance, stage presence, and overall performance. The scoresheet asks, “how do you rate the Elvis tribute artist’s ability to recreate the charisma Elvis had when performing on stage?” It feels perversely unsuitable to use a numerical scale of one to ten to grade the heart pounding, pelvis gyrating, diaphragm contracting, sexual suggestiveness emanating from Elvis’s magnetism. But recreation is a science, and each of the artists has boiled the charm down to exacting little details. Independently, these are superficial and insufficient things: aerosol spray, faux sideburns, rhinestone jumpsuits, and choreographies practiced over and over in the rehearsal room. But, as the aphorism goes, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

![]()

![]()

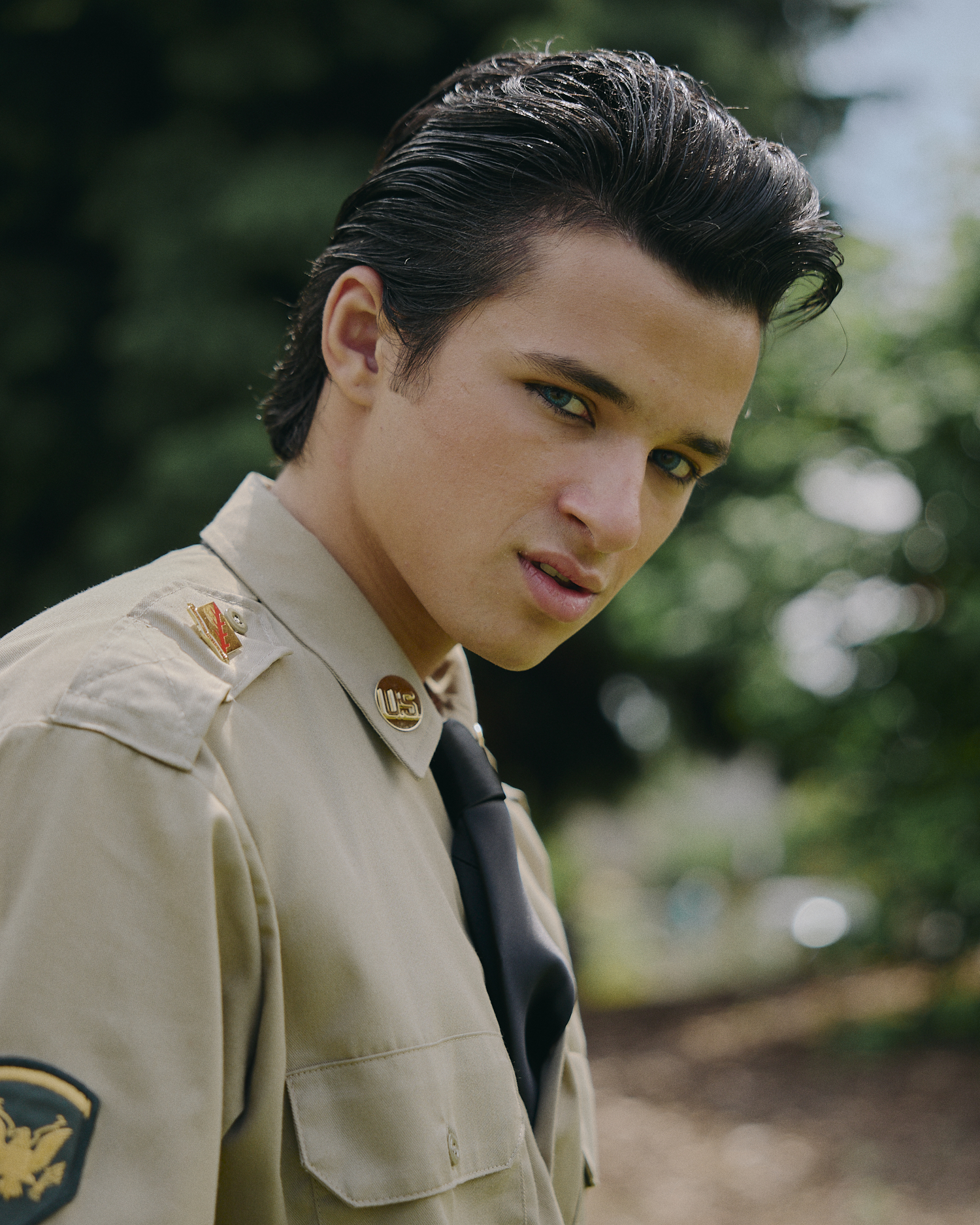

On the festival grounds, love is drifting in the air but it’s also declared in tattoos. On aging skin, inky portraits feather into fine lines with the same soft focus cinematographers used to get with the Vaseline trick in old Hollywood films. “It’s very hard to live up to an image,” Elvis once famously said, and he had many to mirror back. The rockabilly image, the gospel image, the army image, the Vegas image—each mythic persona was remarkably elastic apart from the pouty lips and deep-set eyes that were the signature of his everlasting likeness.

In one of your photos, I see what I think is a tattoo of Elvis on a woman’s arm, but the figure I mistook to be The King is sporting a neck tattoo of a lightning bolt with the letters TCB. This was an emblem Elvis had designed with the motto “taking care of business in a flash,” which he made into gifts for his band to mark their comeback to live performances, after a decade of prioritizing movies. A memorial date appears below the portrait. October 18, 2010. The significance is personal, and hard for me to make out. I search for headlines that might explain the importance but do a poor job and start going through old emails instead. On that day, I see you wrote to me to say you borrowedWhat is Cinema? by André Bazin and were thumbing through it while on set at an abandoned paper factory, doing reshoots for the latest feature in a horror film franchise.

![]()

![]()

![]()

When he was buried, Elvis was wearing a blue shirt, a white suit, and the diamond-encrusted TCB ring. He died, as everyone knows, of cardiac arrest. But there once was a time when the circulatory system was as mysterious as the stars and heavens above. Early cardiovascular physicians believed the ring finger was directly connected to the heart through the vena amoris, or vein of love. There is no such vein, but the conviction was strong enough that the ring finger is still where most people wear their marriage bands today. To Elvis, for whom jewelry was a quintessential part of his image, every finger was a ring finger. Imagine what tenfold passages to the heart could do.

![]()

We didn’t get married by Elvis, but a few weeks after our wedding we found ourselves at his honeymoon getaway. Built in 1960 and nicknamed “The House of Tomorrow,” the architecture features four interlocking circular sections joined under a dramatically sloping winged roof. We had unknowingly arrived two hours early for the tour and the doors were locked so we killed time in the shade on the front lawn. The guide finally arrived, let us in, and flicked on the lights. Once inside, you took a photo through the peephole on the front door, turning the outside world into a fishbowl. I went upstairs and took a photo in the master bedroom, the sugary pink bedding and quilted headboard filling the frame like a mountain of frosting. Downstairs, we sat on a sixty-foot-long beige couch with pillows the color of tangerines and green olives. You balanced the camera on the ledge of the fireplace and set the self-timer, hurrying back to put your arm around me.

This visual story is a piece of observational fiction written by Caitlin Chaisson, inspired by photographs taken by Denis Gutiérrez-Ogrinc at the 2023 Penticton Elvis Festival in British Columbia.

I recently learned that at the Graceland Wedding Chapel, where Elvis Presley didn’t marry Priscilla Beaulieu but once pulled over on South Las Vegas Boulevard to scope it out as a possible venue, the “Loving You” package will set you back $329 not including the officiant’s fee or tips and taxes. I take this as a lesson that even the possibility of a thing that never happened is a reasonable foundation for love.

At the Graceland Chapel, the paperwork for a state marriage license must be completed before the ceremony and the betrothed must show valid government identification. In a brief fifteen minutes, the long road of life is promised to unfurl between the cursive swirls of signatures, in a blissful picture of love and togetherness until that final curtain call. Everything about the act of marriage is beguilingly anachronistic—the forever and the fleeting and the past and the future are knotted together. So, maybe being married by a man who died in 1977 but will surely outlive us all is the resounding peal of love’s complicated timelines.

Years before we met you lived up near this place in the Okanagan in Canada that’s not famous for much but draws a crowd of people for a weekend every summer. Professional and amateur Elvis tribute artists come from all over the world to compete in qualifying rounds for the finals in Memphis, Tennessee, over two thousand miles away. Saggy folding chairs and sweating coolers dot the lawn in front of an outdoor stage with a sound system that can project the classics loud enough to be heard by the audience of silver- haired retirees and their grandchildren. The sun blazes down in the shadowless sage-brushed desert.

A different heat manifests in the set list of the festival’s program handout, which reads like the plot of a passionately dysfunctional relationship. The Wonder of You, Trying to Get to You, My Babe, I Can’t Stop Loving You, You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling, Suspicious Minds, If You Love Me Let Me Know, Don’t Be Cruel, Treat Me Nice, Baby What You Want Me to Do, Burning Love, I’ll Never Fall in Love Again, It’s Over, Can’t Help Falling in Love. Amidst the emotional turmoil, judgment is cast in four categories: vocals, appearance, stage presence, and overall performance. The scoresheet asks, “how do you rate the Elvis tribute artist’s ability to recreate the charisma Elvis had when performing on stage?” It feels perversely unsuitable to use a numerical scale of one to ten to grade the heart pounding, pelvis gyrating, diaphragm contracting, sexual suggestiveness emanating from Elvis’s magnetism. But recreation is a science, and each of the artists has boiled the charm down to exacting little details. Independently, these are superficial and insufficient things: aerosol spray, faux sideburns, rhinestone jumpsuits, and choreographies practiced over and over in the rehearsal room. But, as the aphorism goes, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

On the festival grounds, love is drifting in the air but it’s also declared in tattoos. On aging skin, inky portraits feather into fine lines with the same soft focus cinematographers used to get with the Vaseline trick in old Hollywood films. “It’s very hard to live up to an image,” Elvis once famously said, and he had many to mirror back. The rockabilly image, the gospel image, the army image, the Vegas image—each mythic persona was remarkably elastic apart from the pouty lips and deep-set eyes that were the signature of his everlasting likeness.

In one of your photos, I see what I think is a tattoo of Elvis on a woman’s arm, but the figure I mistook to be The King is sporting a neck tattoo of a lightning bolt with the letters TCB. This was an emblem Elvis had designed with the motto “taking care of business in a flash,” which he made into gifts for his band to mark their comeback to live performances, after a decade of prioritizing movies. A memorial date appears below the portrait. October 18, 2010. The significance is personal, and hard for me to make out. I search for headlines that might explain the importance but do a poor job and start going through old emails instead. On that day, I see you wrote to me to say you borrowedWhat is Cinema? by André Bazin and were thumbing through it while on set at an abandoned paper factory, doing reshoots for the latest feature in a horror film franchise.

When he was buried, Elvis was wearing a blue shirt, a white suit, and the diamond-encrusted TCB ring. He died, as everyone knows, of cardiac arrest. But there once was a time when the circulatory system was as mysterious as the stars and heavens above. Early cardiovascular physicians believed the ring finger was directly connected to the heart through the vena amoris, or vein of love. There is no such vein, but the conviction was strong enough that the ring finger is still where most people wear their marriage bands today. To Elvis, for whom jewelry was a quintessential part of his image, every finger was a ring finger. Imagine what tenfold passages to the heart could do.

We didn’t get married by Elvis, but a few weeks after our wedding we found ourselves at his honeymoon getaway. Built in 1960 and nicknamed “The House of Tomorrow,” the architecture features four interlocking circular sections joined under a dramatically sloping winged roof. We had unknowingly arrived two hours early for the tour and the doors were locked so we killed time in the shade on the front lawn. The guide finally arrived, let us in, and flicked on the lights. Once inside, you took a photo through the peephole on the front door, turning the outside world into a fishbowl. I went upstairs and took a photo in the master bedroom, the sugary pink bedding and quilted headboard filling the frame like a mountain of frosting. Downstairs, we sat on a sixty-foot-long beige couch with pillows the color of tangerines and green olives. You balanced the camera on the ledge of the fireplace and set the self-timer, hurrying back to put your arm around me.

This visual story is a piece of observational fiction written by Caitlin Chaisson, inspired by photographs taken by Denis Gutiérrez-Ogrinc at the 2023 Penticton Elvis Festival in British Columbia.

Caitlin Chaisson is a curator and critic who writes about contemporary art. Her work has been published in Canadian Art, C Magazine, and frieze, among others. She holds an MA from the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College.

Denis Gutiérrez-Ogrinc works professionally in both still and moving image industries. His approach to image-making is informed by storytelling and he uses photography to consider the relationships between people and places. His images have been published in Mob Journal, Flanelle, NUVO, and S/ Magazine, and he has worked collaboratively with independent musicians and fashion brands.